The Crystal Palace, home of the Great Exhibition of 1851, was the first World Fair where Britain showed its industrial might and astute culture.

At the Great Exhibition of 1851, lock-picking competitions first captured the imagination of the British public. These contests pitted rival, brand-name locksmiths against each other in an effort to circumvent the leading security devices of the day, typically before a crowd of onlookers. As such, they presented a spectacle of security – an opportunity for those present to witness the most sophisticated locks not resting dormant, but actually under attack from a skilled and determined mechanic taking the part of the criminal.

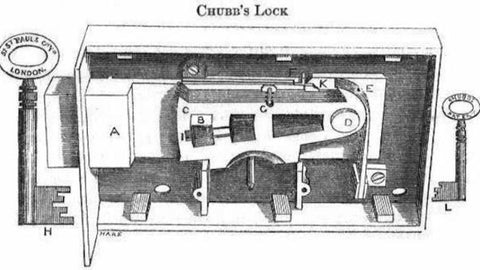

The most celebrated of these lock-pickers was Alfred Charles Hobbs, who first arrived in Britain as a representative of the American lock-making firm Day & Newell, before rising to international acclaim by picking two locks previously considered inviolable: Chubb & Son’s ‘detector lock’, originally patented in 1818; and Bramah & Co.’s famous challenge lock, first patented in 1785.

The latter had stood proudly in the firm’s Piccadilly shop window for decades, alongside a notice offering two hundred guineas to anyone who could devise an implement with which to pick it. Hobbs’s conquest of these two ‘unpickable’ locks captivated the press: one newspaper even asserted that no feature of the Exhibition had attracted greater public attention than this ‘celebrated lock contest’. Yet the ‘Great Lock Controversy’, as it became known, was only the most famous of a series of lock-picking challenges and disputes which issued from the emerging security industry of the 1850s and 1860s.

The history of the security industry – in Britain as elsewhere – remains largely unwritten. Focusing predominantly on state systems of crime control, historians have barely touched upon market responses to crime. However, recent work has begun to shed light on the history of security more broadly defined: Eloise Moss and David Smith have examined the place of security firms within British culture, and how these companies influenced popular understandings of criminality. As such, they have revealed the deep historical roots of anxieties surrounding insecurity, and highlighted the role of security entrepreneurs in shaping commonplace perceptions of risk, responsibility and prevention. But historians have yet to embark upon any broader exploration of security enterprise as a significant aspect of modern social development. For instance, an important theme which the cultural histories noted above tend to gloss over is the commercial logic which informed the provision of security products and services. Thus, despite unraveling the discourse surrounding the Great Lock Controversy in minute detail, Smith never explains why lock-picking competitions took place, nor does he explore their material consequences. Indeed, he purposely evades the latter question by dubiously asserting that the Controversy ‘had more symbolic than real meaning’.

By contrast, this article contributes to a political economy of modern security, grounded in a critical analysis of the mechanisms through which the social power of the security industry was constituted historically. What follows thus examines the rise and fall of the lock-picking competition in terms of its commercial rationale, cultural meanings and social consequences. It draws mainly upon sources in the Chubb & Son lock and safe company archive, particularly its scrapbook collection, the ‘Chubb Collectanea’. It first explains why lock-picking competitions flourished in terms of the marketing strategies of premium lock-makers, before situating public interest in competitive lock-picking in its cultural contexts. Next, it exposes the shortcomings of the competition as a reliable arbiter of security product quality, and as a motor of product development. Lastly, it exposes the cumulative impact of lock-picking contests, both upon the commercial fortunes of lock-making companies, and upon changing attitudes towards security, technology and the market.

The nineteenth century witnessed the transition towards a modern system of security provision, increasingly mediated by products subject to continual technological development, and delivered through the market by assertive, brand-name producers. Lock-picking competitions played an important role in this development, and hence they illuminate a key chapter in the history of modern security. The security industry developed out of advances in lock-making made late in the eighteenth century. Those locks hitherto in general use were constructed with fixed guards or wards – hence known as ‘warded locks’ – the shape of which corresponded to the cut of the matching key-bit.

By the late eighteenth century, these locks were increasingly deemed to provide inadequate protection. As locksmiths worked from a limited range of ward patterns, duplication was prevalent, meaning that multiple keys would operate the same lock. Additionally, warded locks were vulnerable to picking by two methods. First, the wards were easily ‘mapped’ from the keyhole (for example, by inserting a piece of wax against a key blank), to provide the pattern for making a duplicate key. Second, simple hook-shaped lock picks could effectually bypass the wards entirely, and so act directly on the bolt.

An alternative to warded models emerged with the development of ‘tumbler’ or ‘lever’ locks, which incorporated multiple, moving guards. In particular, Barron’s lock (patented in 1778) provided the basis for a host of subsequent design modifications and refinements. By the early nineteenth century, a small collection of firms was engaged in the production of locks on this new principle, and the most successful makers (Bramah and Chubb) already approached the status of household names. Lock picking contests arose within this advanced section of the lock trade – sometimes designated the ‘patent’ lock trade – early in the nineteenth century.

Joseph Bramah’s 200-guinea challenge, which attracted only one (unsuccessful) contestant before 1851, propelled his firm to prominence, while Charles Chubb traded upon a convicted housebreaker frustrated attempt to pick the detector lock in 1824. Yet competitive lock picking developed into a more regular system from 1851, underwritten by two important developments. The first was the emergence of the skilled, technically proficient burglar as among the principal figures of fear in the ‘criminal class’. While the prevalence of burglary and housebreaking had long prompted public concern, by the mid-nineteenth century the burglar was becoming emblematic of a certain kind of ‘professional’ criminality, particularly as interest in other archetypal offenders (notably the juvenile pickpocket) diminished.

The second development was the formation of the international exhibition movement, which vitally invigorated the lock-picking spectacle, and lent it an international dimension. Following Hobbs’s exploits at the Great Exhibition, further (less famous) contests followed, most significantly John Goater’s much-disputed picking of a Hobbs lock in 1854, and Hobbs’s unsuccessful attempt to pick Edwin Cotterill’s ‘climax detector’ lock that same year. The format of individual competitions varied considerably, yet most were held in public, by prior arrangement between the rival lock-makers.

Rewards were sometimes offered as an inducement to challengers, and as an assertion of the maker’s confidence in his product. Generally, the object of a competitions was specifically to pick the lock – to release the bolt without damaging the mechanism – though violent modes of lock-breaking (employing drills and gunpowder) were incorporated from the late 1850s.

In order to flourish, lock-picking competitions had to make commercial sense. Firms making patent locks on the new principle faced competition from the established lock-making industry (centred on the Black Country), which continued to produce the technically inferior – yet far cheaper – warded lock. Warded locks remained widespread throughout the nineteenth century (especially on domestic premises) due to this competitive cost advantage. Hence, the major patent locksmiths promoted their products on grounds of quality, and commonly directed their marketing materials to commercial proprietors with substantial movable property (notably bankers, jewellers and merchants), rather than to private householders. In particular, they had two core marketing priorities. First, they had to convince potential consumers that their product was functionally effective – that the lock really was ‘unpickable’. Secondly, they had to affirm the superiority of their product over its rivals – in other words, that it was more definitely unpickable than others on the market.

These objectives were crucial because consumers could find no guarantee, before purchasing, that a lock would work as promised. Advertisers used various techniques to try to drive home this message: they referred to patents, cited approving testimonials, and reproduced news reports which reflected well upon the product. However, print advertising was a difficult medium through which to instill public confidence in consumer goods. As several historians have argued, ‘puffery’ – the inflated claims widely made by the promoters of various goods – had deleterious consequences for public trust in nineteenth-century advertising.

Such skepticism made alternative, exhibitionist modes of marketing more attractive, for locks as for other technological novelties. However, unlike most cutting-edge devices, one cannot simply exhibit or ‘demonstrate’ a lock to prove its security: a lock cannot be seen to work in isolation, it cannot ‘speak for itself’. Rather, its utility consists in interaction – in frustrating human attempts to manipulate it. For this reason, the lock picking competition emerged as the principal form of exhibitionist marketing in this sector. In theory, lock-picking competitions provided an open, transparent forum in which the relative merits of different products were straightforwardly established. By simulating the risk that locks were designed to protect against (attack by skilled burglars), competitors promised to present a uniquely credible vindication of the lock’s security, and so circumvent charges of puffery. Furthermore, the format of competitions was designed to ensure that trials were conducted rigorously and fairly. Rigor was guaranteed by the commercial interests of the competing parties, with each product tested by a rival manufacturer (or his workmen), with a keen interest in picking it.

Meanwhile, the lock-picker’s conduct was regulated by measures to ensure fair-play: agreements stipulating the terms of contests were generally completed beforehand, and sometimes expert witnesses (typically locksmiths or engineers, nominated by each party) were appointed as jurors or umpires, to ensure the agreement was honored. Lastly, the lock was tested by a skillful operator – a practical locksmith – whose abilities were analogous to the most ‘expert’ of thieves. In these ways, lock-makers tailored lock-picking competitions to their marketing strategy. Commercial motivations were paramount when considering whether to engage in particular challenges. For example, Charles Chubb initiated contests in the early 1830s in order to counter rumours that local locksmiths had picked his detector lock, and so to defend his product’s position in the market.

The publicity of the lock-picking spectacle enabled Chubb to claim the public test as definitive proof of his product’s inviolability, and thus to discredit rumors of private pickings. The need for commercial gain also applied to attempts to pick a rival’s lock. A poster advertising Thomas Parsons’s 1000-guinea challenge of 1837 contains a revealing annotation, presumably by Chubb: ‘it is worth no persons [sic] while to try them [i.e., to attempt to pick Parsons’s locks] for people will not buy them.’

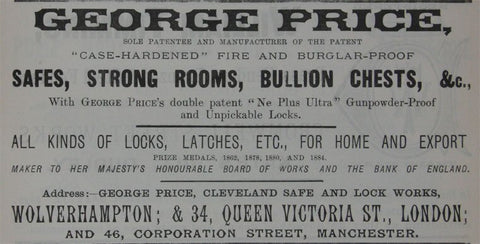

The incentive to compete was perhaps even greater for lesser-known manufacturers: by exposing household names to renewed scrutiny, they could break into this heavily branded trade. For Wolverhampton-based safe-maker George Price – who bemoaned the bias towards well known firms in the London press – exhibitions were ‘the greatest levelers of all the inherited distinctions of the manufacturing classes’, as there ‘the public have the opportunity of comparing the articles exhibited by rival makers with each other, and of drawing their own conclusions accordingly.’ He understood that public competitions carried just the same potential, and so doggedly pursued his arch-rival, Milner & Son, with repeated challenges to a public test of their safes in the 1850s.

Finally, lock-makers were attracted to competitions by the considerable public interest which they generated. As spectacles, they were keenly witnessed, with onlookers sometimes actively participating: when Michael Parnell removed his lock from the Crystal Palace in 1854, to deprive Goater (who was Chubb’s foreman) of another opportunity to pick it, he was greeted by ‘the derisive shouts of a crowd of people.’ However, such episodes notwithstanding, the public were engaged in the competitions primarily through the press. One year after the event, journalists could assert that ‘Most newspaper readers must be more or less familiar with the lock-controversy of 1851’, while another commentator claimed in 1854 that talk of the Hobbs-Goater controversy ‘appears likely to absorb the question of war [in Crimea].’

Evidence of public interest in the competitions comes largely from such statements, issued by journalists themselves, as there is seemingly little mention of them in other documents (except for specialist publications). Yet there are at least hints of a broader popular appeal. For instance, in the early 1850s, Bramah & Co. were apparently forced to withdraw from their shop display an improved lock – presented as a renewed challenge to Hobbs – due to the volume of passers-by making ‘idle applications’ to pick it. In order to understand why the competitions attracted such attention, one must explore their cultural resonances.

Lock-picking contests elicited considerable press comment in large part because they keyed into the popular fascination with technology. Against the backdrop of profound transformation in economic and social life, and Britain’s assumption of international industrial ascendency, technological enthusiasm was a major force in the mid-Victorian period, breeding the cult of the inventor and engineer. Matters of technical and scientific interest stood among the principal topics of the day, for audiences across the social spectrum. This culture proved highly receptive to lock-picking competitions: the weekly press provided extensive design reports on the relevant models, tailored to a readership already at ease with examining the technical specifications of manufactures.

The modern lock was well suited to bear such attention, the intricacy of its moving parts making it ripe for mechanical analysis (and its smallness making it somehow especially appealing). Of course, there were limits to what readers could bear: reviewing Chubb’s display at the International Exhibition of 1862, one newspaper concluded that a description of Chubb’s banker’s lock, ‘however minute, would be of little interest to our readers on account of the unavoidable technicalities needed’.

Nevertheless, lock-picking competitions clearly fed off of the broader press and popular interest in technology at this time. Still more absorbing than the construction of locks was the feat of picking them. The fact that contemporaries understood the modern lock (with its moving parts) as a ‘machine’ imbued the competitions with the intrigue of a battle between mechanical skill and the material product of that skill. The act also carried an air of mystery, never more so than in Hobbs’s 16-day struggle against the Bramah lock, which was conducted behind closed doors. The Illustrated London News – which had previously detailed Hobbs’s tactics in picking Chubb’s detector lock – extensively covered this trial of mechanical skill, providing illustrations of Hobbs’s bespoke lock-picking apparatus, and carefully explicating his method.

As exemplars of ingenuity and determined, competitive effort, lock-picking contests appealed to a technically-attuned public. Attention again focused on Hobbs in 1854, when he tried in vain to pick Edwin Cotterill’s climax detector lock. The lock-picking implement produced on this occasion was formed of a hoop bearing twelve pieces of wire around a central spring; each wire corresponded to a slider in the lock, and each could be operated independently, so as to apply the unique degree of pressure to each individual slider required to operate the mechanism.

The Manchester Guardian noted that this ‘very ingenious construction’ struck those present with ‘surprise and admiration.’ However, critical to the lock-picking spectacle was Hobbs’s use of this remarkable contrivance – his showmanship: In pressing inwards any wire, Mr. Hobbs placed the handle between his lips, and let the end rest against a tooth. The object of this was to test precisely the amount of pressure necessary to force back any given slide, and especially to determine the point at which the effect of pressure terminated. For this purpose, a tooth would be more sensitive than the fingers, as a vibration would be sensibly felt by the tooth the instant resistance was met with.

Such tortuous manipulation of tools and body lent Hobbs’s exploits a certain panache, which excelled that of his rivals, and quickly won him considerable celebrity: by October of 1851, the Morning Chronicle declared that his accomplishments had been so voraciously devoured by the public that he had become ‘an article of general property’.

The lock-picking competition also appealed thanks to its cultural familiarity. A rich culture of scientific display had already sensitized broad sections of British society to such a spectacle. Furthermore, much like (for instance) spectacular electrical demonstrations, lock picking competitions augmented both the locksmith’s personal standing (as a mechanical expert) and the repute of his inventions. This context also explains the ready resort to talk of ‘the science of lock-picking’ in commentary on the competitions. Some contestants – themselves caught up in the culture of ‘scientific’ display and technological enthusiasm – exploited this association between lock-picking and science, forging for themselves a public persona more akin to an experimenter than an entrepreneur. Thus, upon arrival to meet Cotterill’s challenge in 1854, Hobbs declared that he had come, ‘to solve a great mechanical problem’, before proceeding to instruct the assembled crowd in his method.

This ‘science’ of lock-picking was the product of a culture in which science and technology intermingled closely on a public stage. The context of international economic competition was a further factor in generating interest in lock-picking competitions at mid-century. Despite the grand facade of imperial self-confidence, the Great Exhibition was founded on an underlying sense of unease regarding the relative quality of British manufactures and the sustainability of Britain’s global industrial supremacy. Set alongside recent American achievements in naval vessels, reaping machines and firearms, the picking of locks previously considered impregnable threatened further to undermine British confidence in its industrial output. Keen to bolster embattled national pride, The Builder called for the Day & Newell lock to be subject to a similar trial: ‘Is there no public-spirited burglar in London that [sic] will come forward for the honour of his country and a round sum of money?’ While sections of the press – reluctant to admit defeat at the hands of an American – hesitated to verify Hobbs’s accomplishments, reactions were more complex than this, as we have seen.

However, the tendency of the press to defend national honor reasserted itself strongly in 1854: Goater’s picking of one of Hobbs’s locks was thus greeted as a triumphant victory for ‘John Bull’ over ‘Yankeedom’. An outpouring of patriotic comment constituted a kind of collective self-reassurance regarding the viability of British locks – and by extension its manufactures at large – in both domestic and export markets. In fact, there were good grounds for disputing Goater’s achievement. Hobbs was quick to point out that that his lock was picked only after he had himself publicly acknowledged faults in the design; moreover, the article in question was not Hobbs’s celebrated bank lock, but a cheaper model, designed for common drawers and tills.

The fact that most commentators rode roughshod over these details signals their eagerness to mobilize the patriotic potential of a simpler narrative. While lock-picking competitions promised to provide a transparent forum through which to establish the security of the various models, in practice the outcome of individual competitions was anything but transparent. The result of many contests was hotly disputed, producing no clear winners and losers. There were several plausible grounds for challenging an unfavorable outcome. Firstly, while most contests were public spectacles, a few were conducted in private, without any objective adjudication, breeding suspicion regarding the fairness of proceedings. Given that public demonstration or independent verification was vital to validating private knowledge, private pickings threatened to undermine public trust in the competitive process. Indeed, one must ask why lock-makers would engage in such trials – the results of which were bound to be disputed – were they not seeking to circumvent the terms of engagement stipulated for a mutually-agreed contest. Secondly, where prior arrangements between the competitors were lacking, the provenance of the lock under trial was open to question, for the suggestion that the lock-picker had prior access to it fueled suspicion that he may have interfered with its internal arrangement. Thirdly, again where the defending party had not consented to the contest, the quality of the lock itself provided grounds for dispute, as we saw in the case of the Hobbs-Goater controversy.

Yet ambiguity surrounded the result was not confined to such special circumstances; rather, it was endemic in the competitive system. The problem was that competitions were patently artificial scenarios, providing a simulation of burglary and security far removed from real-world conditions. For example, Hobbs took 16 days over picking the Bramah lock, during which time he enjoyed free and exclusive access to it, retaining an instrument in the keyhole throughout – conditions which, Bramah & Co. observed, ‘could only be afforded to an experimentalist.’ Of course, if a lock survived a trial on such generous terms, its reputation was thereby enhanced; yet locks picked under such conditions were not necessarily deficient for practical purposes.

Several observers made this point once the Bramah lock was eventually undone, affirming (Hobbs’s achievement notwithstanding) the ‘practical invulnerability of the lock.’ More generally, George Price asserted that several of the locks picked in the 1850s were in fact tolerably secure. Yet if competitions tended to provide an overly rigorous test of lock-picking, their exclusion of other modes of criminal entry resulted in an insufficiently rigorous simulation of burglary. Referring to the Hobbs-Goater controversy, one journalist wryly observed that ‘Housebreakers…do not interest themselves much in the matter. These nocturnal operators find it as easy to pick a Chubb or a Hobbs, with a jemmy, as the commonest description of lock’.

Similarly, an authority on locks cautioned his readers that ‘thieves do not always confine themselves to the condition of a challenge, in which force and injury to the lock are of course prohibited; and if a lock can be easily opened by tearing out its entrails, it is of very little use to say that it would have defied all the arts of polite lock-picking’.

Clearly, lock-picking competitions did not provide the transparent demonstration of security which consumers would have valued. Unsurprisingly, most contemporaries struggled to divine the moral of a lock-picking contest. As one journalist noted: ‘To pick a lock is an act described in three small words, yet the discussion [surrounding the Great Lock Controversy] shewed [sic] that different persons attached different meanings to the feat so designated.’ With the competitive system failing to provide a clear guide to relative product quality, more conventional authorities – advertisers and journalists – assumed this task. Many in the press took their role as regulators of corporate reputations seriously, yet the need for a mediator to interpret the outcome of competitions undermined the system, thanks to the commercial imperative (to attract advertisers) which influenced how newspapers presented particular businesses, and the tendency of journalists to come to the defense of local and national interests in corporate disputes.

In any case, observers grew just as wary of commercial trickery in competitions as in print advertisements. As one article on the Saxby-Hobbs contest concluded wearily: ‘We much question…whether there be not a good deal of puffery connected with the fine art of lock-picking, as well as with that of lock-making.’ Furthermore, the often bitter language of dispute between rival locksmiths tarnished the veneer of fair play covering competitions. Discord amongst rival inventor-entrepreneurs was perhaps to be expected, given that personal reputations were vital to perceptions of product quality; yet the hostile atmosphere nonetheless had deleterious consequences for public confidence in the competitive system. Referring to the Hobbs-Goater controversy, Punch regretted that it was ‘carried on with extreme acrimony and animosity, accompanied by reciprocal imputations of unfairness and fraud.’ Some felt that, amidst such entrepreneurial posturing, the public interest was lost. One correspondent to The Times in 1851 bemoaned the prolonged war of words between Hobbs and Chubb, and spoke for the bankers and others ‘who are compelled to rely on “patent detectors” and similar locks, [and who] are looking anxiously for more important operations.’

As dispute crowded out objective analysis, all were left vulnerable to charges of favouritism. One reviewer, reflecting approvingly on a volume of Hobbs’s writings published in 1853, noted that it was ‘open to the charge of being a partisan work, but we do not see how this can be avoided; for since the great lock controversy there have been parties for Bramah, for Chubb, and for Hobbs’. Whatever the flaws of lock-picking contests, some still hoped that the competitive pressure they engendered would preempt advances in criminal techniques, leading to improvements in security product design. The first generations of tumbler and lever locks were designed to protect against those risks to which warded locks were vulnerable, especially the use of ‘skeleton picks’, and the practice of ‘mapping’ the mechanism. These methods were adopted in the early competitions, and seemingly for decades British experts regarded them the only viable means of picking a lock.

By contrast, in 1851 Hobbs exploited an apparently new technique, the so-called ‘tentative’ method, by which pressure was applied to the bolt and the levers manipulated sequentially against this pressure, until each aligned to its corresponding notch, allowing the bolt to be thrown. This was precisely the kind of ‘scientific’ procedure, reliant upon mechanical knowledge and aptitude, associated with professional burglary. The mid-century competitions thus exposed British locks to a new threat, yet in a controlled environment, which allowed locksmiths to devise alternative means of protection. Several commentators on the Great Lock Controversy thus looked forward to (preferably British) locksmiths devising ‘some new method of security, based upon some more certain principles However, the relationship between competitions, criminality and security product design was more complex than this suggests. Some contemporaries took almost the opposite view, expressing concern that the publicity of the lock-picking spectacle actually provided instruction to professional burglars. Some journalists purposefully desisted from explaining the methods of competitive lock-pickers, for fear that they would inspire such ‘ingenious’ criminals. Yet others, more deeply troubled by the ethics of competitions, worried that too fine a line separated the ‘science’ of lock-picking from the ‘science’ of burglary.

During the Great Lock Controversy, The Times worried where ‘THE PICK LOCK QUESTION’ would lead: ‘as art always invites imitation, we have no doubt that the taste for lock-picking – which is already quite common enough – will extend among a class where perfection in the operation is not at all to be desired.’ The competitions were thus in danger of dignifying burglary as an ‘artistic experiment.’

While the lock-picking controversies did not confer upon housebreakers the respectable image of an ‘experimentalist’, such concerns illuminate familiar anxieties about whether the education of criminals might serve not just to promote moral progress, but also to sponsor the development of criminal cunning. What about the impact of lock-picking on lock design? Superficially, there were grounds for optimism: the months and years following the Great Lock Controversy witnessed the introduction of improved locks by leading firms, eager to reclaim their place at the summit of the trade. The patent record also attests to a flurry of applications relating to locks in the 1850s. Although the Patent Law Amendment Act of 1852 certainly encouraged applications the rush to protect and promote new lock designs still owed much to the interest generated by the competitions. Several of these designs were intended revolving ‘curtains’ or guards to prevent the insertion of multiple implements through the keyhole, adjusted mechanisms to prevent the continuous application of pressure to the bolt, and added false notches to frustrate the manipulation of tumblers or levers. However, simply making a lock more difficult to pick was hardly the most appropriate design innovation at this time. This was because the ‘science’ of lock-picking developed through the competitions seems not to have been matched by any significant advance in criminal lock picking.

Re-evaluating the Great Lock Controversy some two years on, the Wolverhampton Chronicle observed that despite the ample publicity devoted to Hobbs’s method, ‘no instance has yet occurred of any robbery having been effected through the picking of a Chubb’s lock. Thieves may get through trap doors and gratings, incautiously left insecure, or even break through walls, but a Chubb’s Patent defies them yet’. One might expect such a ringing endorsement from the firm’s local newspaper, yet George Price too, despite making ‘numerous enquiries’, ‘failed to discover a single instance in which a thief has succeeded in picking a good modern lock, which had any real pretensions to security.’ The most celebrated heist of the 1850s – the South-Eastern Railway bullion robbery of 1855 – saw thieves gain access to safes fitted with Chubb locks, yet they did so by making copies from the original keys, not by picking the locks.

The gap between competitive and criminal standards of lock-picking did not mean that property was blissfully secure, rather that thieves were likely to resort to alternative, simpler modes of entry. As we have seen, contemporaries were well aware of the lock-picking competition’s shortcomings as a simulation of burglary. Moreover, by elevating lock-picking above other modes of criminal attack, the competitions may even have stifled more appropriate product development. The first cautionary signs came in the late 1850s, when a series of high-profile safe-breakings, effected with the aid of drills, fuelled anxieties that advances in criminal skill had hastened beyond improvements in security product design. The safe-makers promptly resorted to spectacular drilling demonstrations to reassure the public that new modifications would keep the burglars at bay.

However, a more substantial blow to the security industry came with the Cornhill burglary of 1865. This sensational case concerned a break-in at Mr Walker’s jeweler's shop in the City of London, accomplished in spite of the proprietor’s scrupulous attention to security, and the regular patrol of the police. Significantly, the burglars made no attempt upon the lock of the Milner safe – whether with picks, drills or gunpowder – but instead attacked the safe itself, repeatedly hammering metal wedges into the frame before wrenching the door open. The success of this approach revealed systemic failings in security product design, resulting in no small part from the system of public competitions.

To a considerable extent, competitive lock-picking contests made the security companies preoccupied with locks, to the neglect of safe design. (Indeed, the usual format of competitions in the early 1850s exposed only the keyhole of the lock, deliberately precluding alternative modes of attack.) Hence, lock-picking competitions failed to keep security product design in step with advances in criminal methods. As the Standard observed in 1865: In regard to locks we seem certainly to have beaten the rogues, and the time necessary for picking the best of these contrivances is more than the burglar can dare to reckon upon. But as love laughs at the locksmiths, so roguery lays down the ‘twirl’ [skeleton key] and picks up the lever, wrenching away the fastenings by main force, thus as it were turning the flank of the defensive enemy. Upon the whole there seems to be a conviction among mechanical authorities that the safe-makers have a good deal to learn.

The threat of the ‘modern’ burglar had shifted decisively from competitive simulation to the real world; in place of Hobbs, Thomas Caseley – the leader of the Cornhill gang – came to symbolize the threat of ‘scientific’ criminality. * Given such a sorry record of dispute and disappointment, did the lock-picking contests simply fuel public distrust and anxiety? Smith seems to think so, arguing that the Great Lock Controversy produced a ‘crisis’ in mid-Victorian security by upsetting established commercial reputations, undermining national pride, and corroding the ethic of individual self-reliance.

The episode left contemporaries ambivalent: according to The Builder, Hobbs had ‘certainly done something to restore the public confidence in locks, as well as much to destroy that confidence.’ However, there was no substantive crisis in security in the 1850s, for if the consequences of successful pickings were partly destructive, they were also undeniably creative: one prominent locksmith observed in the mid-1860s that the Great Lock Controversy ‘gave a stimulus to the lock trade, such as it has never received before or since.’

As we have seen, lock-picking sustained lock-making: it spurred the introduction of new models and provided a means for younger firms to gain traction in this heavily branded trade. Furthermore, by hastening the perceived obsolescence of old locks at a time of limited progress in criminal lock-picking, the competitions promoted renewed, ‘upgrade’ consumption of the latest models. Hence even the likes of Chubb & Son, whose lock was publicly picked, profited from competitions nonetheless. The Great Lock Controversy had little immediate impact upon the firm’s sales figures, yet the competition era was clearly a period of considerable commercial expansion for Chubb, and almost certainly for the industry at large.

The transition to more favorable economic conditions in the 1850s played its part, yet the scale of growth at Chubb – its trade account roughly doubled in value between the years 1850-51 and 1860-61, as did sales revenue – signals the buoyancy of premium lock-making at this time. Hence, at the heart of the lock-picking competitions lay a productive potential, which was substantively realized in the mid-nineteenth century.

Furthermore, lock-picking competitions had a tangible impact on attitudes towards security at mid-century. While the contests failed to establish a single ‘market leading’ product, they promoted the modern lock in general as an article of security, and elevated it to a new-found prominence and prestige in British culture. Traces of this interest were already present early in the nineteenth century, yet only following the Great Exhibition did locks became a topic almost of polite conversation. Dalton observed that ‘public attention has been forcibly and permanently fixed on a subject [locks] which, at the opening of the Exhibition, seemed one of the least likely to obtain any large share of consideration.’

Chamber’s Edinburgh Journal fleshed out the nature of this transformation more fully: A LOCK, until within the last year or two, has been generally regarded as a mere piece of ironmongery – a plain matter-of-fact appendage to a door – a thing in which carpenters and box-makers are chiefly interested….A locksmith is [was] viewed like any other smith – as a hammerer and a filer of bits of iron….Suddenly, however, the subject has become invested with a dignity not before accorded to it: it has risen almost to the rank of a science. Learned professors, skillful engineers, wealthy capitalists, dexterous machinists, all have paid increased respect to locks….In short, a lock, like a watch or a steam-engine, is a machine whose construction rests on principles worthy of study, in the same degree that the lock itself is important as an aid to security.

Through the competitions, the lock had ascended from a banal ‘piece of ironmongery’ to a mechanical marvel: contemporaries referred to a successor to steam power and to the ‘unpickable’ lock in the same breath, considering each a ‘great desideratum’ of the age. This transformation ensured extensive coverage of lock design and lock-making, even in mainstream newspapers, for years to come; only later in the century, as public interest in security products focused increasingly on safes and strong rooms, did the lock commence its retreat back to dull familiarity.

Less obviously, competitive lock-picking contributed to a subtle shift in how the development of security technologies was understood. By 1851, both the Chubb and Bramah locks had long been considered permanently unpickable. As far as any distinct view prevailed, security product development was conceived in terms of a stadial progression, which advanced from primitive methods of construction, through warded locks, to the telos of the ‘unpickable’ locks of the nineteenth century. To be sure, long after the heyday of competitions, lock-makers continued to regurgitate the myth of the ‘unpickable’ lock – assuring ‘absolute’ or ‘perfect’ security – which, of course, they claimed to have invented. Some ventured still bolder assertions that, with their inventions, the history of lock-making was effectively at an end.

In 1862, during a protracted dispute with a rival inventor, Cotterill asserted ‘that it is rather too late in the history of my locks to dispute their security’. He evidently took Hobbs’s unsuccessful attempt eight years previously as definitive proof of the model’s permanent inviolability. Such promises seemed increasingly empty as the 1850s progressed, due to two factors: first, the apparent violation of a series of ‘unpickable’ locks (whether made by Chubb, Bramah or Hobbs) in competition; and second, the revelation of new modes of attack, both the tentative mode of picking and alternative, destructive methods. Thus the stadial narrative of security product development was progressively undermined. While some simply posited the Great Exhibition as a new watershed, a more modern conception of continuous development in security product design was also emerging. Hobbs thus critiqued Cotterill’s claim that his lock had already been proven unpickable, arguing that all products required rigorous public testing to ensure that they remained of sufficient quality to frustrate the burglars of the day. This notion of the co-evolution of security products and criminal techniques would acquire firmer foundation following the high-profile burglaries of the late 1850s and 1860s.

In this shifting context, the lock-picking contests also contributed something to a new conception of how security was to be provided in a modern society. Besides elevating the lock to a new fame and dignity, the competitions served to reify it, as a privileged provider of security. With the threat of professional criminality crystallizing around the burglar, lock picking competitions exhibited a technological ‘fix’ for this problem, and thus presented an alternative solution to serious property crime distinct from collective police provision or any amelioration of prevailing social conditions.

By aligning deep-seated social interests in safeguarding property with modern security devices, the competitions furthered their consumption and dissemination, as we have seen. Unsurprisingly, therefore, one finds at this time signs of an increasing resort to new security commodities to protect wealth, particularly within the business community. Indeed, following the Cornhill burglary, the excessive reliance of commercial proprietors on locks and safes (as well as on police patrols) became a major point of public discussion. Significantly, this enthusiasm for security devices advanced specifically in the 1850s, a moment at which faith in the preventative efficacy of the criminal justice system was coming under strain. Property crime proved a persistent menace, despite a generation or more of experiment with ‘new’ forms of law-enforcement (professional policing) and penal discipline (the penitentiary). Many had previously regarded the potential of such ‘enlightened’ criminal justice policy for moral regeneration with almost Utopian confidence; by mid-century, however, they were increasingly disillusioned.

In this context, the invitation to invest in modern locks – as the latest innovation in crime prevention – the same dreams of perfect, mechanical, systematic protection carried greater momentum. Yet one must keep such developments in perspective. The tendency further to transpose security provision onto the world of commodities remained only a tendency; new locks were integrated into existing forms of collective and personal security provision, without competing with them. Additionally, the myth of achieving ‘perfect’ security through consumption – a myth nurtured by the competitions – was effectually exposed by the Cornhill case. It would thus seem that, in itself, the propensity to reify security commodities is rather fragile, as these products are ever in danger of having their professed ‘burglar-proof’ qualities exposed, with consumers invited to peer behind the veil of assurance.

Finally, the competitions facilitated the emergence of a modern security industry. However ambiguous the result of individual contests, the cumulative spectacle of rival manufacturers pitted in close competition reflected positively on modern locksmiths. In place of the rather static picture of a couple of untouchable firms with inviolable products, the competitions introduced the public to a collection of companies, which constituted a dynamic industry, capable of securing private property in a period of rapid social change.

Out of the rupture in the established brand hierarchy came a more volatile set of competing commercial interests: as the Spectator observed, Before the exhibition of 1851 no one thought of making a lock, save Bramah and Chubb. They were the orthodox makers, and men believed in them. The American Hobbs dispelled the illusion, and set the lock-making trade free. Since this emancipation, various makers have entered the lists, vying with each other especially in the strength and security of their locks.

In propagating this image, the lock-picking contests gave substance to the notion that a significant measure of security might effectually be provided through the competitive motor of industrial capitalism. Irrespective of the transitory fortunes of individual firms, the security industry as a whole emerged from the era of competitions as a recognizable guardian of private property. The lock-picking contest receded rapidly in the late 1860s. The lock-makers remained enthusiastic followers of the exhibition circuit, yet lock-picking competitions had virtually disappeared by 1870. We have already seen that competitions were neither uniform nor unchanging; by the 1860s, safes were increasingly the object of challenges, which now featured drills and gunpowder besides lock-picks. Yet the object of competition had remained the lock itself. The Cornhill burglary disturbed this continuity, causing an immediate transformation of the competitive format, and ultimately squeezing spectacular display into a more marginal position within British security industry practice. The wedging of the Milner safe at Cornhill – with utter disregard for the (un)pickability of the lock – forced a reconceptualization of burglars’ tactics. The Times noted that, in the 1850s, ‘it was believed that an iron safe with a first-rate lock would bid defiance to burglars. Two years ago, however, that delusion was exploded on the occasion of the celebrated Cornhill robbery.’

The resulting changes to public competitions were apparent by the ‘Battle of the Safes’ at the Paris Exhibition of 1867, which pitted the American safe-maker Silas Herring against his Lancashire counterpart Samuel Chatwood, in a robust and much-disputed test of the ‘burglary-proof’ qualities of their respective safes. The tests deployed reflected a post Cornhill conception of criminal tactics: despite a perfunctory attempt on both sides to pick the locks, the ‘battle’ rapidly descended into a trial of strength, with extensive use of wedges, drills and sledgehammers on the doors and frames.

The days of agonizing over a lock, picks in hand, were over. Yet the shift from lock-picks to heavy tools robbed the competitive spectacle of half its charm. True, some commentators were impressed by the physique and skill of Chatwood’s hammer-wielding men, but the mystery and artistry of Hobbs had all but evaporated. Exhibitions, demonstrations and the occasional public contest would recur in the security industry into the twentieth century, but the mid-Victorian system of public competitions, inaugurated as recently as 1851, was already obsolete by 1870. Competitive lock-picking thus receded, yet not before it had established the security industry as a social force, revitalized the market in security products and subtly reshaped public attitudes towards protection. In these ways, the competitions were integral to the nineteenth-century transformation in the provision of security commodities, a transition which would have far reaching and lasting consequences.

Reproduced here by kind permission of David Churchill

Images added by Chris Dangerfield.

Happy Picking.